AceDeceiver: Breaking Apple’s Cryptographic Leash

On March 16, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiThe past week, I’ve been writing all about cryptographic leashes and how they could be easily broken in the case of controlling FBI’s iOS backdoor. Surprisingly, the first serious example of this has surfaced this week. The researchers at Palo Alto Networks, who have been killing it lately with great iOS research, did a breakdown of a piece of Chinese malware known as AceDeceiver. AceDeceiver breaks the cryptographic leash baked into the iPhone’s App Store system, allowing an attacker to install applications on the host iPhone even after they’ve been revoked by Apple. While the malware, in its present form, isn’t likely to cause widespread damage, the vulnerabilities in Apple’s DRM that this presents could be used for far more malicious purposes.

AceDeceiver starts its life as malware on your desktop. In its present form, you’d have to be dumb enough to install a Chinese pirate app store in order to have to worry about this, but in a more malicious form, something like it could potentially be embedded as a trojan in legitimate software. The malware performs a man-in-the-middle attack between your computer and the App Store, and fudges the authorizations used to let your iPhone run purchased software. Think of the attack as forging a receipt, like paying for a set of towels at Target, then returning a different set. Apple has no way to check the towels (your apps) to make sure they’re the same ones, so the iPhone lets the app run since you have a valid receipt. It’s even worse than this, because the receipts aren’t tied to your iTunes account – you can pull someone else’s receipt out of the trash and return towels you never purchased. It’s this receipt that is re-used to install the malware’s own software on your iPhone by impersonating iTunes. The malware author can use his or her own receipts to load previously approved App Store software onto your phone.

Apple vs. FBI: Where We Are Now, and Where We’re Going

On March 15, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiMuch has happened since a California magistrate court originally granted an order for Apple to assist the FBI under the All Writs Act. For one, most of us now know what the All Writs Act is: An ancient law that was passed before the Fourth Amendment even existed, now somehow relevant to modern technology a few hundred years later. Use of this act has exploded into a legal argument about whether or not it grants carte blanche rights of the government to demand anything and everything from private companies (and incidentally, individuals) if it helps them prosecute crimes. Of course, that’s just the tip of the iceberg. We’ve seen strong debates about whether any person should be allowed to have private conversations, thoughts, or ideas that can’t later be searched, whether forcing others to work for the government violates the constitution, whether other countries will line up to exploit technology if America does, and ultimately – at the heart of all of these – whether fear of the word “terrorism” is enough to cause us all to burn our constitution.

Over the past few weeks, the entire tech community has gotten behind Apple, filing a barrage of friend-of-the-court briefs on Apple’s behalf. Security experts such as myself, Crypto “Rock Stars”, constitutionalists, technologists, lawyers, and 30 Helens all agree that Apple is in the right, and that backdooring iOS would cause irreparable damage to the security, privacy, and safety of hundreds of millions of diplomats, judges, doctors, CEOs, teenage girls, victims of crimes, parents, celebrities, politicians, and all men and women around the world. Throughout the past month, legal exchanges have escalated from ice cold to white hot, and from professional to a traveling flea circus as ridiculous terms such as “lying dormant cyber pathogen” have been introduced. Congress, the courts, and the public have seen strong technical and legal arguments, impassioned pleas from victims, attempts at reason by the law enforcement community, name calling, proverbial mugs-thrown-across-the-room, uncontrollable profanity on media briefings, and just about any other form of pressure manifesting itself that one can imagine.

A Bomb on a Leash

On March 13, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiThe idea of a controlled explosion comes to mind when I think about pending proceedings with Apple. The Department of Justice argues that a backdoored version of iOS can be controlled in that Apple’s existing security mechanisms can prevent it from blowing up any device other than Farook’s. This is quite true. The code signing and TSS signing mechanism used to install firmware have controls that can most certainly bind a firmware bundle to a given device UDID. What’s not true is the amount of real control and protection this provides.

Think of Apple’s signing mechanisms as a kind of “leash” if you will; they provide a means of digital rights management to control any payload delivered onto the device. Where the DOJ’s argument falls into error is that their focus is too much on this leash, and too little on the payload itself. The payload in this scenario is a modified version of iOS that has a direct line into a device’s security mechanisms to both disable them and manipulate them to rapidly brute force a passcode (remotely, mind you). It’s the electronic equivalent of an explosive for an iPhone that will blow the safe open (FBI’s analogy, not mine). What Apple is being forced to design, develop, test, validate, and protect is essentially a bomb on a leash.

Apple Should Own The Term “Warrant Proof”

On March 11, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiThe Department of Justice, in a March 10 filing, accused Apple of outrightly making “warrant proof” devices, and accused Apple of obstruction of justice by making these devices so secure that they could not be searched, even with a warrant. While these words belonged to DOJ, I think Apple should own them. If you study our state laws, federal laws, and international treaties, you’ll see many examples of intellectual property that actually are protected against warrants. Yes, there are things in this country that are deemed warrant proof.

As per The State Department, Article 27.3 of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations states, a diplomatic pouch “shall not be opened or detained”. In other words, it’s warrant proof. No law enforcement agency in our country is permitted – under international treaty – to open a diplomatic pouch, and any warrants issued are null and void. Guidelines even permit for unaccompanied diplomatic pouches that are traveling without a diplomat or courier, which even further emphasizes the impetus for security of such pouches: they should have locks, and strong ones at that. Do we still have spying? Absolutely, and it’s illegal. It is not only reasonable then, but important to have a device like the iPhone – secure against illegal search and seizure.

An Example of “Warrant-Friendly Security”

On March 11, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiThe encryption on the iPhone is clearly doing its job. Good encryption doesn’t discriminate between attackers, it simply protects data – that’s its job, and it’s frustrating both criminals and law enforcement. The government has recently made arguments insisting that we must find a “balance” between protecting your privacy and providing a method for law enforcement to procure evidence with a warrant. If we don’t, the Department of Justice and the President himself have made it clear that such privacy could easily be legislated out of our products. Some think having a law enforcement backdoor is a good idea. Here, I present an example of what “warrant friendly” security looks like. It already exists. Apple has been using it for some time. It’s integrated into iCloud’s design.

Unlike the desktop backups that your iPhone makes, which can be encrypted with a backup password, the backups sent to iCloud are not encrypted this way. They are absolutely encrypted, but differently, in a way that allows Apple to provide iCloud data to law enforcement with a subpoena. Apple had advertised iCloud as “encrypted” (which is true) and secure. It still does advertise this today, in fact, the same way it has for the past few years:

“Apple takes data security and the privacy of your personal information very seriously. iCloud is built with industry-standard security practices and employs strict policies to protect your data.”

So with all of this security, it sure sounds like your iCloud data should be secure, and also warrant friendly – on the surface, this sounds like a great “balance between privacy and security”. Then, the unthinkable happened.

CIS Files Amici Curiae Brief in Apple Case

On March 3, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiCIS sought to file a friend-of-the-court, or “amici curiae,” brief in the case today. We submitted the brief on behalf of a group of experts in iPhone security and applied cryptography: Dino Dai Zovi, Charlie Miller, Bruce Schneier, Prof. Hovav Shacham, Prof. Dan Wallach, Jonathan Zdziarski, and our colleague in CIS’s Crypto Policy Project, Prof. Dan Boneh. CIS is grateful to them for offering up

Shoot First, Ask Siri Later

On February 26, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiYou know the old saying, “shoot first, ask questions later”. It refers to the notion that careless law enforcement officers can often be short sighted in solving the problem at hand. It’s impossible to ask questions to a dead person, and if you need answers, that really makes it hard for you if you’ve just shot them. They’ve just blown their only chance of questioning the suspect by failing to take their training and good judgment into account. This same scenario applies to digital evidence. Many law enforcement agencies do not know how to properly handle digital evidence, and end up making mistakes that cause them to effectively kill their one shot of getting the answers they need.

In the case involving Farook’s iPhone, two things went wrong that could have resulted in evidence being lifted off the device.

First, changing the iCloud password prevented the device from being able to push an iCloud backup. As Apple’s engineers were walking FBI through the process of getting the device to start sending data again, it became apparent that the password had been changed (suggesting they may have even seen the device try to authorize on iCloud). If the backup had succeeded, there would be very little, if anything, that could have been gotten off the phone that wouldn’t be in the iCloud backup.

Secondly, and equally damaging to the evidence, was that the device was apparently either shut down or allowed to drain after it was seized. Shutting the device down is a common – but outdated – practice in field operations. Modern device seizure not only requires that the device should be kept powered up, but also to tune all of the protocols leading up to the search and seizure so that it’s done quickly enough to prevent the battery from draining before you even arrive on scene. Letting the device power down effectively shot the suspect dead by removing any chances of doing the following:

Apple’s Burden to Protect or Perpetually Create a “Weapon”

On February 25, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiAs the Apple/FBI dispute continues on, court documents reveal the argument that Apple has been providing forensic services to law enforcement for years without tools being hacked or leaked from Apple. Quite the contrary, information is leaked out of Foxconn all the time, and in fact some of the software and hardware tools used to hack iOS products over the past several years (IP-BOX, Pangu, and so on) have originated in China, where Apple’s manufacturing process takes place. Outside of China, jailbreak after jailbreak has taken advantage of vulnerabilities in iOS, some with the help of tools leaked out of Apple’s HQ in Cupertino. Devices have continually been compromised and even today, Apple’s security response team releases dozens of fixes for vulnerabilities that have been exploited outside of Apple. Setting all of this aside for a moment, however, lets take a look at the more immediate dangers of such statements.

By affirming that Apple can and will protect such a backdoor, Comey’s statement is admitting that Apple will be faced with not only the burden of breathing this forensics backdoor into existence, but must also take perpetual steps to protect it once it’s been created. In other words, the courts are forcing Apple to create what would be considered a weapon under the latest proposed Wassenaar rules, and charging them with the burden of also preventing that weapon from getting out – either the code itself, or the weaknesses that Apple would have to continue allowing to be baked into their products to allow the weapon to work.

On Ribbons and Ribbon Cutters

On February 23, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiWith most non-technical people struggling to make sense of the battle between FBI and Apple, Bill Gates introduced an excellent analogy to explain cryptography to the average non-geek. Gates used the analogy of encryption as a “ribbon around a hard drive”. Good encryption is more like a chastity belt, but since Farook decided to use a weak passcode, I think it’s fair here to call it a ribbon. In any case, lets go with Gates’ ribbon analogy.

Where Gates is wrong is that the courts are not ordering Apple to simply cut the ribbon. In fact, I think there would be more in the tech sector who would support Apple simply breaking the weak password that Farook chose to use if this had been the case. Apple’s encryption is virtually unbreakable when you use a strong alphanumeric passcode, and so by choosing to use a numeric pin, you get what you deserve.

Instead of cutting the ribbon, which would be a much simpler task, the courts are ordering Apple to invent a ribbon cutter – a forensic tool capable of cutting the ribbon for FBI, and is promising to use it on just this one phone. In reality, there’s already a line beginning to form behind Comey should he get his way. NY DA Cy Vance has stated that NYC has 175 iPhones waiting to be unlocked (which translates to roughly 1/10th of 1% of all crime in NYC for an entire year). Documents have also shown DOJ has over a dozen more such requests pending. If the promise of “just this one phone” were authentic, there would be no need to order Apple to make this ribbon cutter; they’d simply tell them to cut the ribbon.

Dumpster Diving in Forensic Science

On February 22, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiRecent speculation has been made about a plan to unlock Farook’s iPhone simply so that they can walk through the evidence right on the device, rather than to forensically image the device, which would provide no information beyond what is already in an iCloud backup. Going through the applications by hand on an iPhone is along the dumpster level of forensic science, and let me explain why.

The device in question appears to have been powered down already, which has frozen the crypto as well as a number of processes on the device. While in this state, the data is inaccessible – but at least it’s in suspended animation. At the moment, the device is incapable of connecting to a WiFi network, running background tasks, or giving third party applications access to their own data for housekeeping. This all changes once the device is unlocked. Now when a pin code is brute forced, the task is actually running from a separate copy of the operating system booted into memory. This creates a sterile environment where the tasks on the device itself don’t start, but allows a platform to break into the device. This is how my own forensics tools used to work on the iPhone, as well as some commercial solutions that later followed my design. The device can be safely brute forced without putting data at risk. Using the phone is a different story.

On FBI’s Interference with iCloud Backups

On February 21, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiIn a letter emailed from FBI Press Relations in the Los Angeles Field Office, the FBI admitted to performing a reckless and forensically unsound password change that they acknowledge interfered with Apple’s attempts to re-connect Farook’s iCloud backup service. In attempting to defend their actions, the following statement was made in order to downplay the loss of potential forensic data:

“Through previous testing, we know that direct data extraction from an iOS device often provides more data than an iCloud backup contains. Even if the password had not been changed and Apple could have turned on the auto-backup and loaded it to the cloud, there might be information on the phoen that would not be accessible without Apple’s assistance as required by the All Writs Act Order, since the iCloud backup does not contain everything on an iPhone.”

This statement implies only one of two possible outcomes:

Apple, FBI, and the Burden of Forensic Methodology

On February 18, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiRecently, FBI got a court order that compels Apple to create a forensics tool; this tool would let FBI brute force the PIN on a suspect’s device. But lets look at the difference between this and simply bringing a phone to Apple; maybe you’ll start to see the difference of why this is so significant, not to mention underhanded.

First, let me preface this with the fact that I am speaking from my own personal experience both in the courtroom and working in law enforcement forensics circles since around 2008. I’ve testified as an expert in three cases in California, and many others have pleaded out or had other outcomes not requiring my testimony. I’ve spent considerable time training law enforcement agencies around the world specifically in iOS forensics, met LEOs in the middle of the night to work on cases right off of airplanes, gone through the forensics validation process and clearance processes, and dealt with red tape and all the other terrible aspects of forensics that you don’t see on CSI. It was a lot of fun but was also an incredibly sobering experience, as I have not been trained to deal with the evidence (images, voicemail, messages, etc) that I’ve been exposed to like LEOs have; my faith has kept me grounded. I’ve developed an amazing amount of respect for what they do.

For years, the government could come to Apple with a warrant and a phone, and have the manufacturer provide a disk image of the device. This largely worked because Apple didn’t have to hack into their phones to do this. Up until iOS 8, the encryption Apple chose to use in their design was easily reversible when you had code execution on the phone (which Apple does). So all through iOS 7, Apple only needed to insert the key into the safe and provide FBI with a copy of the data.

Code is Law

On February 17, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiFor the first time in Apple’s history, they’ve been forced to think about the reality that an overreaching government can make Apple their own adversary. When we think about computer security, our threat models are almost always without, but rarely ever within. This ultimately reflects through our design, and Apple is no exception. Engineers working on encryption projects are at a particular disadvantage, as the use (or abuse) of their software is becoming gradually more at the mercy of legislation. The functionality of encryption based software boils down to its design: is its privacy enforced through legislation, or is it enforced through code?

My philosophy is that code is law. Code should be the angry curmudgeon that doesn’t even trust its creator, without the end user’s consent. Even at the top, there may be outside factors affecting how code is compromised, and at the end of the day you can’t trust yourself when someone’s got a gun to your head. When the courts can press the creator of code into becoming an adversary against it, there is only ultimately one design conclusion that can be drawn: once the device is provisioned, it should trust no-one; not even its creator, without direct authentication from the end user.

tl;dr technical explanation of #ApplevsFBI

On February 17, 2016 by Jonathan Zdziarski- Apple was recently ordered by a magistrate court to assist the FBI in brute forcing the PIN of a device used by the San Bernardino terrorists.

- The court ordered Apple to develop custom software for the device that would disable a number of security features to make brute forcing possible.

- Part of the court order also instructed Apple to design a system by which pins could be remotely sent to the device, allowing for rapid brute forcing while still giving Apple plausible deniability that they hacked a customer device in a literal sense.

- All of this amounts to the courts compelling Apple to design, develop, and protect a backdoor into iOS devices.

Tl;Dr Notes on iOS 8 PIN / File System Crypto

On June 8, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiHere’s iOS file system / PIN encryption as I understand it. I originally pastebin’d this but folks thought it was worth keeping around. (Thanks to Andrey Belenko for his suggestions for edits).

Block 0 of the NAND is used as effaceable storage and a series of encryption “lockers” are stored on it. This is the portion that gets wiped when a device is erased, as this is the base of the key hierarchy. These lockers are encrypted with a hardware key that is derived from a unique hardware id fused into the secure space of the chip (secure enclave, on A7 and newer chipsets). Only the hardware AES routines have access to this key, and there is no known way to extract it without chip deconstruction.

One locker, named EMF!, stores the encryption key that makes the file system itself readable (that is, directory and file structure, but not the actual content). This key is entirely hardware dependent and is not entangled with the user passcode at all. Without the passcode, the directory and file structure is readable, including file sizes, timestamps, and so on. The only thing not included, as I said. Is the file content.

Another locker, called BAGI, contains an encryption key that encrypts what’s called the system keybag. The keybag contains a number of encryption “class keys” that ultimately protect files in the user file system; they’re locked and unlocked at different times, depending on user activity. This lets developers choose if files should get locked when the device is locked, or stay unlocked after they enter their PIN, and so on. Every file on the file system has its own random file key, and that key is encrypted with a class key from the keybag. The keybag keys are encrypted with a combination of the key in the BAGI locker and the user’s PIN. NOTE: The operating system partition is not encrypted with these keys, so it is readable without the user passcode

There’s another locker in the NAND (what Apple calls the class 4 key, and what we call the DKEY). The DKEY is not encrypted with the user PIN, and in previous versions of iOS (<8), was used as the foundation for encryption of any files that were not specifically protected with “data protection”. Most of the file system at the time used the Dkey instead of a class key, by design. Because the PIN wasn’t involved in the crypto (like it is with the class keys in the keybag), anyone with root level access (such as Apple) could easily open that Dkey locker, and therefore decrypt the vast majority of the file system that used it for encryption. The only files that were protected with the PIN up until iOS 8 were those with data protection explicitly enabled, which did not include a majority of Apple’s files storing personal data. In iOS 8, Apple finally pulled the rest of the file system out of the Dkey locker and now virtually the entire file system is using class keys from the keybag that *are* protected with the user’s PIN. The hardware-accelerated AES crypto functions allow for very fast encryption and decryption of the entire hard disk making this technologically possible since the 3GS, however for no valid reason whatsoever (other than design decisions), Apple decided not to properly encrypt the file system until iOS 8.

Running Invisible in the Background in iOS 8

On March 17, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiSince iOS 8’s release, a number of security improvements have been made since publishing my findings last July. Many services that posed a threat to user privacy have been since closed off, and are only open in beta versions of iOS. One small point I made in the paper was the threat that invisible software poses on the operating system:

“Malicious software does not require a device be jail- broken in order to run. … With the simple addition of an SBAppTags property to an application’s Info.plist (a required file containing descriptive tags iden- tifying properties of the application), a developer can build an application to be hidden from the user’s GUI (SpringBoard). This can be done to a non-jailbroken device if the attacker has purchased a valid signing certificate from Apple. While advanced tools, such as Xcode, can detect the presence of such software, the application is invisible to the end-user’s GUI, as well as in iTunes. In addition to this, the capability exists of running an application in the background by masquerading as a VoIP client (How to maintain VOIP socket connection in background) or audio player (such as Pandora) by add- ing a specific UIBackgroundModes tag to the same property list file. These two features combined make for the perfect skeleton for virtually undetectable spyware that runs in the background.”

As of iOS 8, Apple has closed off the SBAppTags feature set so that applications cannot use that to hide applications, however it looks like there are still some ways to manipulate the operating system into hiding applications on the device. I have contacted Apple with the specific technical details and they have assured me that the problem has been fixed in iOS 8.3. As for now, however, it looks like iOS 8.2 and lower are still vulnerable to this attack. The attack allows for software to be loaded onto a non-jailbroken device (which typically requires a valid pairing, or physical possession of the device) that runs in the background and invisibly to the SpringBoard user interface.

The presence of a vulnerability such as this should heighten user awareness that invisible software may still be installed on a non-jailbroken device, and would be capable of gathering information that could be used to track the user over a period of time. If you suspect that malware may be running on your device, you can view software running invisibly with a copy of Xcode. Unlike the iPhone’s UI and iTunes, invisible software that is installed on the device will show up under Xcode’s device organizer.

Testing for the Strawhorse Backdoor in Xcode

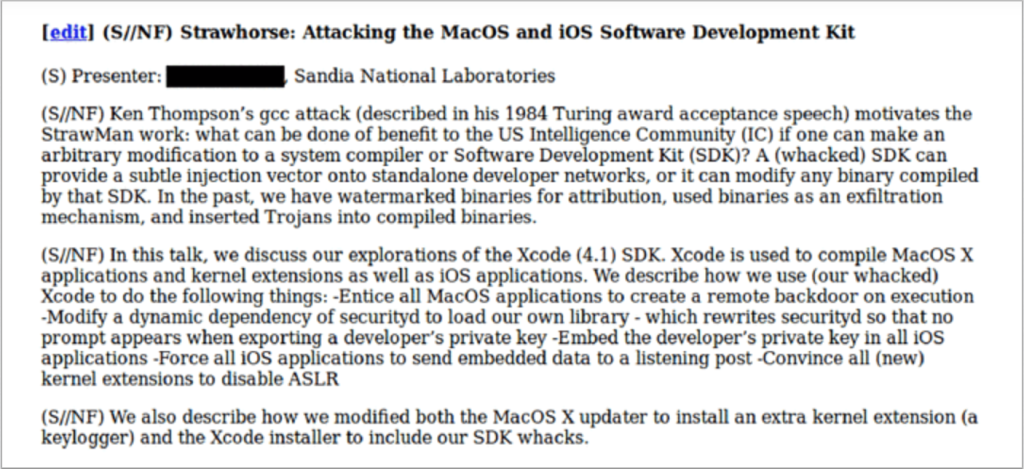

On March 10, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiIn the previous blog post, I highlighted the latest Snowden documents, which reveal a CIA project out of Sandia National Laboratories to author a malicious version of Xcode. This Xcode malware targeted App Store developers by installing a backdoor on their computers to steal their private codesign keys.

So how do you test for a backdoor you’ve never seen before? By verifying that the security mechanisms it disables are working correctly. Based on the document, the malware apparently infects Apple’s securityd daemon to prevent it from warning the user prior to exporting developer keys:

“… which rewrites securityd so that no prompt appears when exporting a developer’s private key”

A good litmus test to see if securityd has been compromised in this way is to attempt to export your own developer keys and see if you are prompted for permission.

The Implications of CIA’s Jamboree

On March 10, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiEarly this morning, The Intercept posted several documents pertaining to CIA’s research into compromising iOS devices (along with other things) through Sandia National Laboratories, a major research and development contractor to the government. The documents outlined a number of project talks taking place at a closed government conference referred to as the Jamboree in 2012. The projects listed in the documents included the following pieces.

Rocoto

Rocoto, a chip-like implant that would likely be soldered to the 30-pin connector on the main board, and act like a flasher box that performs the task of jailbreaking a device using existing public techniques. Once jailbroken, a chip like Rocoto could easily install and execute code on the device for persistent monitoring or other forms of surveilance. Upon firmware restore, a chip like Rocoto could simply re-jailbreak the device. Such an implant could have likely worked persistently on older devices (like the 3G mentioned), however the wording of the document (“we will discuss efforts”) suggests the implant was not complete at the time of the talk. This may, however, have later been adopted into the DROPOUTJEEP implant, which was portrayed as an operational product in the NSA’s catalog published several months ago. The DROPOUTJEEP project, however, claimed to be software-based, where Rocoto seems to have involved a physical chip implant.

Strawhorse

Strawhorse, a malicious implementation of Xcode, where App Store developers (likely not suspected of any crimes) would be targeted, and their dev machines backdoored to give CIA injection capabilities into compiled applications. The malicious Xcode variant was capable of stealing the developer’s private codesign keys, which would be smuggled out with compiled binaries. It would also disable securityd so that it would not warn the developer that this was happening. The stolen keys could later be used to inject and sign payloads into the developer’s own products without their permission or knowledge, which could then be widely disseminated through the App Store channels. This could include trojans or watermarks, as the document suggests. With the developer keys extracted, binary modifications could also be made at a later time, if such an injection framework existed.

In spite of what The Intercept wrote, there is no evidence that Strawhorse was slated for use en masse, or that it even reached an operational phase.

NOTE: At the time these documents were reportedly created, a vast majority of App Store developers were American citizens. Based on the wording of the document, this was still in the middle stages of development, and an injection mechanism (the complicated part) does not appear to have been developed yet, as there was no mention of it.

Lenovo’s Domain Record Appears Jacked

On February 25, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiEarly reports came in from Verge that Lenovo was hacked, however upon visiting the website, many reported no problems. Lenovo servers were not, in fact hacked, however it appears that the lenovo.com domain record may have been hijacked. Two whois queries below show that the domain was updated today and its name servers were changed over from

CVF: SPF as a Certificate Validator for SSL

On February 23, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiIn light of recent widespread MiTM goings on with Superfish and Lenovo products, I dusted off an old technique introduced in the anti-spam communities several years ago that would have prevented this, and could more importantly put a giant dent in the capabilities of government sponsored SSL MiTM.

The Core Problem

The core of the problem with SSL is twofold; after all these years, thousands of Snowden documents, and more reason to distrust governments and be paranoid about hackers more than ever, we’re still putting an enormous amount of trust into certificate authorities to:

- Play by the rules according to their own verification policies and never be socially engineered

- Never honor any secret FISA court order to issue a certificate for a targeted organization

- Be secure enough to never be compromised, or to always know when they’ve been compromised

- Never hire any rogue employees who would issue false certificates

Not only are we putting an immense trust in our CAs, but we’re also putting even more trust into our own computers, and that the root certificates loaded into our trust store are actually trustworthy. Superfish proved that to not be the case, however Superfish has only done what we’ve been doing in the security community for years to conduct pen-tests: insert a rogue certificate into the trust store of a device. We’ve done this with iOS, OSX, Windows PCs, and virtually every other operating system as well in conducting pen-tests and security audits.

Sure, there is cert pinning, you say… however in most cases, when it comes to web browsers at least, cert pinning only pins your certificate to a trusted certificate authority. In the case of Superfish’s malware, cert pinning doesn’t appear to have prevented the interception of SSL traffic whatsoever. In fact, Superfish broke the root store so badly, that in some cases, self-signed certificates could even validate! In the case of CAs that have been compromised (either by an adversary, or via secret court orders), cert pinning can also be rendered ineffective, because it still primarily depends on trusting the CA and the root store.

We have existing solid means of validating the chain of trust, but SSL is still missing one core component, and that’s a means of validating with the (now trusted) host itself, to ensure that it thinks there’s nothing fishy about your connection. Relying on the trust store alone is why, after potentially tens of thousands of website visits, none of the web browsers thought to ask, “hey why am I seeing the same cert on every website I visit?”