An Example of “Warrant-Friendly Security”

On March 11, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiThe encryption on the iPhone is clearly doing its job. Good encryption doesn’t discriminate between attackers, it simply protects data – that’s its job, and it’s frustrating both criminals and law enforcement. The government has recently made arguments insisting that we must find a “balance” between protecting your privacy and providing a method for law enforcement to procure evidence with a warrant. If we don’t, the Department of Justice and the President himself have made it clear that such privacy could easily be legislated out of our products. Some think having a law enforcement backdoor is a good idea. Here, I present an example of what “warrant friendly” security looks like. It already exists. Apple has been using it for some time. It’s integrated into iCloud’s design.

Unlike the desktop backups that your iPhone makes, which can be encrypted with a backup password, the backups sent to iCloud are not encrypted this way. They are absolutely encrypted, but differently, in a way that allows Apple to provide iCloud data to law enforcement with a subpoena. Apple had advertised iCloud as “encrypted” (which is true) and secure. It still does advertise this today, in fact, the same way it has for the past few years:

“Apple takes data security and the privacy of your personal information very seriously. iCloud is built with industry-standard security practices and employs strict policies to protect your data.”

So with all of this security, it sure sounds like your iCloud data should be secure, and also warrant friendly – on the surface, this sounds like a great “balance between privacy and security”. Then, the unthinkable happened.

On Dormant Cyber Pathogens and Unicorns

On March 3, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiGary Fagan, the Chief Deputy District Attorney for San Bernardino County, filed an amicus brief to the court in defense of the FBI compelling Apple to backdoor Farook’s iPhone. In this brief, DA Michael Ramos made the outrageous statement that Farook’s phone might contain a “lying dormant cyber pathogen”, a term that doesn’t actually exist in computer science, let alone in information security.

CIS Files Amici Curiae Brief in Apple Case

On March 3, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiCIS sought to file a friend-of-the-court, or “amici curiae,” brief in the case today. We submitted the brief on behalf of a group of experts in iPhone security and applied cryptography: Dino Dai Zovi, Charlie Miller, Bruce Schneier, Prof. Hovav Shacham, Prof. Dan Wallach, Jonathan Zdziarski, and our colleague in CIS’s Crypto Policy Project, Prof. Dan Boneh. CIS is grateful to them for offering up

Mistakes in the San Bernardino Case

On March 2, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiMany sat before Congress yesterday and made their cases for and against a backdoor into the iPhone. Little was said, however, of the mistakes that led us here before Congress in the first place, and many inaccurate statements went unchallenged.

The most notable mistake the media has caught onto has been the blunder of changing the iCloud password on Farook’s account, and Comey acknowledged this mistake before Congress.

“As I understand from the experts, there was a mistake made in that 24 hours after the attack where the [San Bernardino] county at the FBI’s request took steps that made it hard—impossible—later to cause the phone to back up again to the iCloud,”

Comey’s statements appear to be consistent with court documents all suggesting that both Apple and the FBI believed the device would begin backing up to the cloud once it was connected to a known WiFi network. This essentially established that I nterference with evidence ultimately led to the destruction of the trusted relationship between the device and its iCloud account, which prevented evidence from being available. In other words, the mistake of trying to break into the safe caused the safe to lock down in a way that made it more difficult to get evidence out of it

Shoot First, Ask Siri Later

On February 26, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiYou know the old saying, “shoot first, ask questions later”. It refers to the notion that careless law enforcement officers can often be short sighted in solving the problem at hand. It’s impossible to ask questions to a dead person, and if you need answers, that really makes it hard for you if you’ve just shot them. They’ve just blown their only chance of questioning the suspect by failing to take their training and good judgment into account. This same scenario applies to digital evidence. Many law enforcement agencies do not know how to properly handle digital evidence, and end up making mistakes that cause them to effectively kill their one shot of getting the answers they need.

In the case involving Farook’s iPhone, two things went wrong that could have resulted in evidence being lifted off the device.

First, changing the iCloud password prevented the device from being able to push an iCloud backup. As Apple’s engineers were walking FBI through the process of getting the device to start sending data again, it became apparent that the password had been changed (suggesting they may have even seen the device try to authorize on iCloud). If the backup had succeeded, there would be very little, if anything, that could have been gotten off the phone that wouldn’t be in the iCloud backup.

Secondly, and equally damaging to the evidence, was that the device was apparently either shut down or allowed to drain after it was seized. Shutting the device down is a common – but outdated – practice in field operations. Modern device seizure not only requires that the device should be kept powered up, but also to tune all of the protocols leading up to the search and seizure so that it’s done quickly enough to prevent the battery from draining before you even arrive on scene. Letting the device power down effectively shot the suspect dead by removing any chances of doing the following:

Apple’s Burden to Protect or Perpetually Create a “Weapon”

On February 25, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiAs the Apple/FBI dispute continues on, court documents reveal the argument that Apple has been providing forensic services to law enforcement for years without tools being hacked or leaked from Apple. Quite the contrary, information is leaked out of Foxconn all the time, and in fact some of the software and hardware tools used to hack iOS products over the past several years (IP-BOX, Pangu, and so on) have originated in China, where Apple’s manufacturing process takes place. Outside of China, jailbreak after jailbreak has taken advantage of vulnerabilities in iOS, some with the help of tools leaked out of Apple’s HQ in Cupertino. Devices have continually been compromised and even today, Apple’s security response team releases dozens of fixes for vulnerabilities that have been exploited outside of Apple. Setting all of this aside for a moment, however, lets take a look at the more immediate dangers of such statements.

By affirming that Apple can and will protect such a backdoor, Comey’s statement is admitting that Apple will be faced with not only the burden of breathing this forensics backdoor into existence, but must also take perpetual steps to protect it once it’s been created. In other words, the courts are forcing Apple to create what would be considered a weapon under the latest proposed Wassenaar rules, and charging them with the burden of also preventing that weapon from getting out – either the code itself, or the weaknesses that Apple would have to continue allowing to be baked into their products to allow the weapon to work.

On Ribbons and Ribbon Cutters

On February 23, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiWith most non-technical people struggling to make sense of the battle between FBI and Apple, Bill Gates introduced an excellent analogy to explain cryptography to the average non-geek. Gates used the analogy of encryption as a “ribbon around a hard drive”. Good encryption is more like a chastity belt, but since Farook decided to use a weak passcode, I think it’s fair here to call it a ribbon. In any case, lets go with Gates’ ribbon analogy.

Where Gates is wrong is that the courts are not ordering Apple to simply cut the ribbon. In fact, I think there would be more in the tech sector who would support Apple simply breaking the weak password that Farook chose to use if this had been the case. Apple’s encryption is virtually unbreakable when you use a strong alphanumeric passcode, and so by choosing to use a numeric pin, you get what you deserve.

Instead of cutting the ribbon, which would be a much simpler task, the courts are ordering Apple to invent a ribbon cutter – a forensic tool capable of cutting the ribbon for FBI, and is promising to use it on just this one phone. In reality, there’s already a line beginning to form behind Comey should he get his way. NY DA Cy Vance has stated that NYC has 175 iPhones waiting to be unlocked (which translates to roughly 1/10th of 1% of all crime in NYC for an entire year). Documents have also shown DOJ has over a dozen more such requests pending. If the promise of “just this one phone” were authentic, there would be no need to order Apple to make this ribbon cutter; they’d simply tell them to cut the ribbon.

Dumpster Diving in Forensic Science

On February 22, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiRecent speculation has been made about a plan to unlock Farook’s iPhone simply so that they can walk through the evidence right on the device, rather than to forensically image the device, which would provide no information beyond what is already in an iCloud backup. Going through the applications by hand on an iPhone is along the dumpster level of forensic science, and let me explain why.

The device in question appears to have been powered down already, which has frozen the crypto as well as a number of processes on the device. While in this state, the data is inaccessible – but at least it’s in suspended animation. At the moment, the device is incapable of connecting to a WiFi network, running background tasks, or giving third party applications access to their own data for housekeeping. This all changes once the device is unlocked. Now when a pin code is brute forced, the task is actually running from a separate copy of the operating system booted into memory. This creates a sterile environment where the tasks on the device itself don’t start, but allows a platform to break into the device. This is how my own forensics tools used to work on the iPhone, as well as some commercial solutions that later followed my design. The device can be safely brute forced without putting data at risk. Using the phone is a different story.

On FBI’s Interference with iCloud Backups

On February 21, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiIn a letter emailed from FBI Press Relations in the Los Angeles Field Office, the FBI admitted to performing a reckless and forensically unsound password change that they acknowledge interfered with Apple’s attempts to re-connect Farook’s iCloud backup service. In attempting to defend their actions, the following statement was made in order to downplay the loss of potential forensic data:

“Through previous testing, we know that direct data extraction from an iOS device often provides more data than an iCloud backup contains. Even if the password had not been changed and Apple could have turned on the auto-backup and loaded it to the cloud, there might be information on the phoen that would not be accessible without Apple’s assistance as required by the All Writs Act Order, since the iCloud backup does not contain everything on an iPhone.”

This statement implies only one of two possible outcomes:

10 Reasons Farook’s Work Phone Likely Won’t Have Any Evidence

On February 18, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiTen reasons to consider about Farook’s work phone:

Apple, FBI, and the Burden of Forensic Methodology

On February 18, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiRecently, FBI got a court order that compels Apple to create a forensics tool; this tool would let FBI brute force the PIN on a suspect’s device. But lets look at the difference between this and simply bringing a phone to Apple; maybe you’ll start to see the difference of why this is so significant, not to mention underhanded.

First, let me preface this with the fact that I am speaking from my own personal experience both in the courtroom and working in law enforcement forensics circles since around 2008. I’ve testified as an expert in three cases in California, and many others have pleaded out or had other outcomes not requiring my testimony. I’ve spent considerable time training law enforcement agencies around the world specifically in iOS forensics, met LEOs in the middle of the night to work on cases right off of airplanes, gone through the forensics validation process and clearance processes, and dealt with red tape and all the other terrible aspects of forensics that you don’t see on CSI. It was a lot of fun but was also an incredibly sobering experience, as I have not been trained to deal with the evidence (images, voicemail, messages, etc) that I’ve been exposed to like LEOs have; my faith has kept me grounded. I’ve developed an amazing amount of respect for what they do.

For years, the government could come to Apple with a warrant and a phone, and have the manufacturer provide a disk image of the device. This largely worked because Apple didn’t have to hack into their phones to do this. Up until iOS 8, the encryption Apple chose to use in their design was easily reversible when you had code execution on the phone (which Apple does). So all through iOS 7, Apple only needed to insert the key into the safe and provide FBI with a copy of the data.

Code is Law

On February 17, 2016 by Jonathan ZdziarskiFor the first time in Apple’s history, they’ve been forced to think about the reality that an overreaching government can make Apple their own adversary. When we think about computer security, our threat models are almost always without, but rarely ever within. This ultimately reflects through our design, and Apple is no exception. Engineers working on encryption projects are at a particular disadvantage, as the use (or abuse) of their software is becoming gradually more at the mercy of legislation. The functionality of encryption based software boils down to its design: is its privacy enforced through legislation, or is it enforced through code?

My philosophy is that code is law. Code should be the angry curmudgeon that doesn’t even trust its creator, without the end user’s consent. Even at the top, there may be outside factors affecting how code is compromised, and at the end of the day you can’t trust yourself when someone’s got a gun to your head. When the courts can press the creator of code into becoming an adversary against it, there is only ultimately one design conclusion that can be drawn: once the device is provisioned, it should trust no-one; not even its creator, without direct authentication from the end user.

tl;dr technical explanation of #ApplevsFBI

On February 17, 2016 by Jonathan Zdziarski- Apple was recently ordered by a magistrate court to assist the FBI in brute forcing the PIN of a device used by the San Bernardino terrorists.

- The court ordered Apple to develop custom software for the device that would disable a number of security features to make brute forcing possible.

- Part of the court order also instructed Apple to design a system by which pins could be remotely sent to the device, allowing for rapid brute forcing while still giving Apple plausible deniability that they hacked a customer device in a literal sense.

- All of this amounts to the courts compelling Apple to design, develop, and protect a backdoor into iOS devices.

Tl;Dr Notes on iOS 8 PIN / File System Crypto

On June 8, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiHere’s iOS file system / PIN encryption as I understand it. I originally pastebin’d this but folks thought it was worth keeping around. (Thanks to Andrey Belenko for his suggestions for edits).

Block 0 of the NAND is used as effaceable storage and a series of encryption “lockers” are stored on it. This is the portion that gets wiped when a device is erased, as this is the base of the key hierarchy. These lockers are encrypted with a hardware key that is derived from a unique hardware id fused into the secure space of the chip (secure enclave, on A7 and newer chipsets). Only the hardware AES routines have access to this key, and there is no known way to extract it without chip deconstruction.

One locker, named EMF!, stores the encryption key that makes the file system itself readable (that is, directory and file structure, but not the actual content). This key is entirely hardware dependent and is not entangled with the user passcode at all. Without the passcode, the directory and file structure is readable, including file sizes, timestamps, and so on. The only thing not included, as I said. Is the file content.

Another locker, called BAGI, contains an encryption key that encrypts what’s called the system keybag. The keybag contains a number of encryption “class keys” that ultimately protect files in the user file system; they’re locked and unlocked at different times, depending on user activity. This lets developers choose if files should get locked when the device is locked, or stay unlocked after they enter their PIN, and so on. Every file on the file system has its own random file key, and that key is encrypted with a class key from the keybag. The keybag keys are encrypted with a combination of the key in the BAGI locker and the user’s PIN. NOTE: The operating system partition is not encrypted with these keys, so it is readable without the user passcode

There’s another locker in the NAND (what Apple calls the class 4 key, and what we call the DKEY). The DKEY is not encrypted with the user PIN, and in previous versions of iOS (<8), was used as the foundation for encryption of any files that were not specifically protected with “data protection”. Most of the file system at the time used the Dkey instead of a class key, by design. Because the PIN wasn’t involved in the crypto (like it is with the class keys in the keybag), anyone with root level access (such as Apple) could easily open that Dkey locker, and therefore decrypt the vast majority of the file system that used it for encryption. The only files that were protected with the PIN up until iOS 8 were those with data protection explicitly enabled, which did not include a majority of Apple’s files storing personal data. In iOS 8, Apple finally pulled the rest of the file system out of the Dkey locker and now virtually the entire file system is using class keys from the keybag that *are* protected with the user’s PIN. The hardware-accelerated AES crypto functions allow for very fast encryption and decryption of the entire hard disk making this technologically possible since the 3GS, however for no valid reason whatsoever (other than design decisions), Apple decided not to properly encrypt the file system until iOS 8.

Running Invisible in the Background in iOS 8

On March 17, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiSince iOS 8’s release, a number of security improvements have been made since publishing my findings last July. Many services that posed a threat to user privacy have been since closed off, and are only open in beta versions of iOS. One small point I made in the paper was the threat that invisible software poses on the operating system:

“Malicious software does not require a device be jail- broken in order to run. … With the simple addition of an SBAppTags property to an application’s Info.plist (a required file containing descriptive tags iden- tifying properties of the application), a developer can build an application to be hidden from the user’s GUI (SpringBoard). This can be done to a non-jailbroken device if the attacker has purchased a valid signing certificate from Apple. While advanced tools, such as Xcode, can detect the presence of such software, the application is invisible to the end-user’s GUI, as well as in iTunes. In addition to this, the capability exists of running an application in the background by masquerading as a VoIP client (How to maintain VOIP socket connection in background) or audio player (such as Pandora) by add- ing a specific UIBackgroundModes tag to the same property list file. These two features combined make for the perfect skeleton for virtually undetectable spyware that runs in the background.”

As of iOS 8, Apple has closed off the SBAppTags feature set so that applications cannot use that to hide applications, however it looks like there are still some ways to manipulate the operating system into hiding applications on the device. I have contacted Apple with the specific technical details and they have assured me that the problem has been fixed in iOS 8.3. As for now, however, it looks like iOS 8.2 and lower are still vulnerable to this attack. The attack allows for software to be loaded onto a non-jailbroken device (which typically requires a valid pairing, or physical possession of the device) that runs in the background and invisibly to the SpringBoard user interface.

The presence of a vulnerability such as this should heighten user awareness that invisible software may still be installed on a non-jailbroken device, and would be capable of gathering information that could be used to track the user over a period of time. If you suspect that malware may be running on your device, you can view software running invisibly with a copy of Xcode. Unlike the iPhone’s UI and iTunes, invisible software that is installed on the device will show up under Xcode’s device organizer.

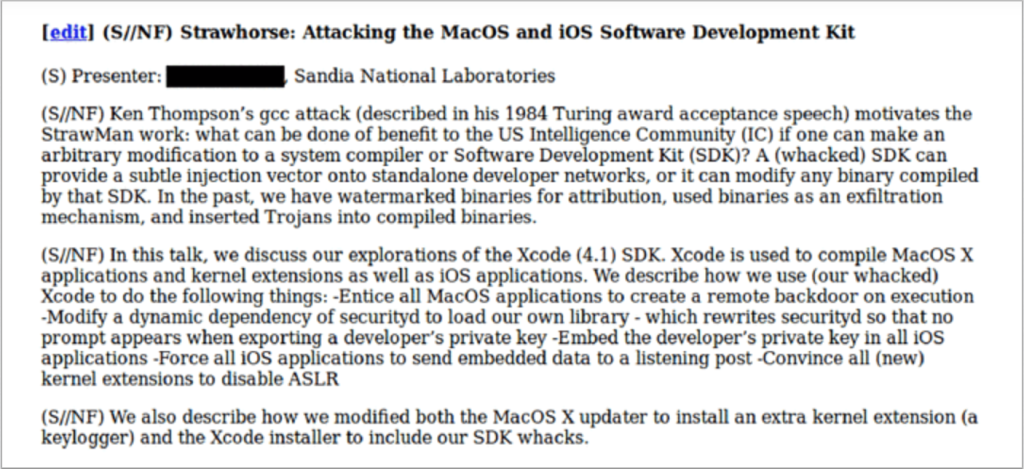

Testing for the Strawhorse Backdoor in Xcode

On March 10, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiIn the previous blog post, I highlighted the latest Snowden documents, which reveal a CIA project out of Sandia National Laboratories to author a malicious version of Xcode. This Xcode malware targeted App Store developers by installing a backdoor on their computers to steal their private codesign keys.

So how do you test for a backdoor you’ve never seen before? By verifying that the security mechanisms it disables are working correctly. Based on the document, the malware apparently infects Apple’s securityd daemon to prevent it from warning the user prior to exporting developer keys:

“… which rewrites securityd so that no prompt appears when exporting a developer’s private key”

A good litmus test to see if securityd has been compromised in this way is to attempt to export your own developer keys and see if you are prompted for permission.

The Implications of CIA’s Jamboree

On March 10, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiEarly this morning, The Intercept posted several documents pertaining to CIA’s research into compromising iOS devices (along with other things) through Sandia National Laboratories, a major research and development contractor to the government. The documents outlined a number of project talks taking place at a closed government conference referred to as the Jamboree in 2012. The projects listed in the documents included the following pieces.

Rocoto

Rocoto, a chip-like implant that would likely be soldered to the 30-pin connector on the main board, and act like a flasher box that performs the task of jailbreaking a device using existing public techniques. Once jailbroken, a chip like Rocoto could easily install and execute code on the device for persistent monitoring or other forms of surveilance. Upon firmware restore, a chip like Rocoto could simply re-jailbreak the device. Such an implant could have likely worked persistently on older devices (like the 3G mentioned), however the wording of the document (“we will discuss efforts”) suggests the implant was not complete at the time of the talk. This may, however, have later been adopted into the DROPOUTJEEP implant, which was portrayed as an operational product in the NSA’s catalog published several months ago. The DROPOUTJEEP project, however, claimed to be software-based, where Rocoto seems to have involved a physical chip implant.

Strawhorse

Strawhorse, a malicious implementation of Xcode, where App Store developers (likely not suspected of any crimes) would be targeted, and their dev machines backdoored to give CIA injection capabilities into compiled applications. The malicious Xcode variant was capable of stealing the developer’s private codesign keys, which would be smuggled out with compiled binaries. It would also disable securityd so that it would not warn the developer that this was happening. The stolen keys could later be used to inject and sign payloads into the developer’s own products without their permission or knowledge, which could then be widely disseminated through the App Store channels. This could include trojans or watermarks, as the document suggests. With the developer keys extracted, binary modifications could also be made at a later time, if such an injection framework existed.

In spite of what The Intercept wrote, there is no evidence that Strawhorse was slated for use en masse, or that it even reached an operational phase.

NOTE: At the time these documents were reportedly created, a vast majority of App Store developers were American citizens. Based on the wording of the document, this was still in the middle stages of development, and an injection mechanism (the complicated part) does not appear to have been developed yet, as there was no mention of it.

Superfish Spyware Also Available for iOS and Android

On February 20, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiFor those watching the Superfish debacle unfold, you may also be interested to note that Superfish has an app titled LikeThat available for iOS and Android. The app is a visual search tool apparently for finding furniture that you like (whatever). They also have other visual search apps for pets and other idiotic things, all of which seem to be quite popular. Taking a closer look at the application, it appears as though they also do quite a bit of application tracking, including reporting your device’s unique identifier back to an analytics company. They’ve also taken some rather sketchy approaches to how they handle photos so as to potentially preserve the EXIF data in them, which can include your GPS position and other information.

To get started, just taking a quick look at the binary using ‘strings’ can give you some sketchy information. Here are some of the URLs in the binary:

Pawn Storm Fact Check

On February 15, 2015 by Jonathan ZdziarskiFortinet recently published a blog entry analyzing the Pawn Storm malware for iOS. There were some significant inaccuracies, however, and since Fortinet seems to be censoring website comments, I thought I’d post my critique here. Here are a few things important to note about the analysis that were grossly inaccurate.

First of important note is the researcher’s claim that the LSRequiresIPhoneOS property indicates that iPads are not targeted, but that the malware only runs on iPhone. Anyone who understands the iOS environment knows that the LSRequiresIPhoneOS tag simply indicates that the application is an iOS application; this tag can be set to true, and an application can still support iPad and any other iOS based devices (iPod, whatever). I mention this because anyone reading this article may assume that their iPad or iPod is not a potential target, and therefore never check it. If you suspect you could be a target of Pawn Storm, you should check all of your iOS based devices.

Second important thing to note: Most of the information the researcher claims the application gathers can only be gathered on jailbroken devices. This is because the jailbreak process in and of itself compromises Apple’s own sandbox in order to allow applications to continue to run correctly after Cydia has relocated crucial operating system files onto the user data partition. When running Cydia for the first time, several different folders get moved to the /var/stash folder on the user partition. Since this folder normally would not be accessible outside of Apple’s sandbox, the geniuses writing jailbreaks decided to break Apple’s sandbox so that you could run your bootleg versions of Angry Birds. Smart, huh?

What You Need to Know About WireLurker

On November 5, 2014 by Jonathan ZdziarskiMobile Security company Palo Alto Networks has released a new white paper titled WireLurker: A New Era in iOS and OS X Malware. I’ve gone through their findings, and also managed to get a hold of the WireLurker malware to examine it first-hand (thanks to Claud Xiao from Palo Alto Networks, who sent them to me). Here’s the quick and dirty about WireLurker; what you need to know, what it does, what it doesn’t do, and how to protect yourself.

How it Works

WireLurker is a trojan that has reportedly been circulated in a number of Chinese pirated software (warez) distributions. It targets 64-bit Mac OS X machines, as there doesn’t appear to be a 32-bit slice. When the user installs or runs the pirated software, WireLurker waits until it has root, and then gets installed into the operating system as a system daemon. The daemon uses libimobiledevice. It sits and waits for an iOS device to be connected to the desktop, and then abuses the trusted pairing relationship your desktop has with it to read its serial number, phone number, iTunes store identifier, and other identifying information, which it then sends to a remote server. It also attempts to install malicious copies of otherwise benign looking apps onto the device itself. If the device is jailbroken and has afc2 enabled, a much more malicious piece of software gets installed onto the device, which reads and extracts identifying information from your iMessage history, address book, and other files on the device.

WireLurker appears to be most concerned with identifying the device owners, rather than stealing a significant amount of content or performing destructive actions on the device. In other words, WireLurker seems to be targeting the identities of Chinese software pirates.